Lumbar puncture

Author: Julia Dixon MD and David Richards MD

Editor: Tom Morrissey MD PhD

Lumbar puncture is a common emergency department procedure. It is most commonly used diagnostically to detect CNS infections, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and inflammatory processes. It can also be therapeutic in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension

(IIH, or pseudotumor cerebri). Before performing a lumbar puncture providers must be well versed in different approaches to the procedure and be aware of potential complications. As with any procedure, good preparation is key to a successful

outcome.

Objectives

This module will prepare you to:

- List the indications for LP

- Explain the risks and benefits involved in obtaining informed consent

- Describe the procedure technique

- Order and interpret lab studies on the CSF

- List complications

- Recognize special considerations in select patients

Indications for lumbar puncture

- Signs and symptoms concerning for meningitis (bacterial, viral, fungal, and tubercular)

- Altered mental status without other clear etiology

- Suspicion for subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Symptoms of multiple sclerosis or Guillan-Barre syndrome

- Relieve symptoms of IIH

Contraindications

- Coagulopathy (including oral anticoagulants)

- Thrombocytopenia (typically platelets less than 20,000 warrant transfusion before the procedure)

- Known intracranial process causing mass effect

- Cellulitis or abscess of skin over the procedure site

- Suspected spinal epidural abscess

Obtaining informed consent

Informed consent should be obtained in the patient’s primary language. The provider should use simple terms understandable to the patient and clearly explain why the procedure is indicated and describe the procedure. The risks of the procedure include

post LP headache (10-30%), epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, damage to nerves, paraparesis, subtonsilar herniation (<1%), radicular symptoms, epidermoid tumor, persistent CSF leak and a dry tap. You should be clear that significant complications

are very rare and clarify the benefits of the procedure, as well as list alternatives.

Procedure technique

A good video of performing a lumbar puncture can be found in the New England Journal Of Medicine’s collection of procedural videos.

The first step is to gather supplies. Many facilities stock premade kits containing most supplies except sterile gloves. It is always good to have an extra needle and additional local anesthetic.

| Sterile Gloves | Collection Tubes (4) |

| Mask | Monometer with 3 way valve |

| Betadine or chlorhexadine | 5cc Syringe |

| Local anesthesia-Lidocaine 1or 2% | 18G or blunt needle |

| Sterile Drape or Towel | 25G or 27G needle |

| Spinal Needle *** | Systemic analgesia |

*** Ideally 20G or 22G – larger needles are associated with increased risk of post LP headache and persistent CSF leak. Spinal needles come in different lengths and are specifically made with occluding stylets to prevent the cutting effect of the needle tip as it penetrates the dura. Some have special tips (ex: Whitacre or Sprotte) thought to spread the dural fibers instead of cutting them.

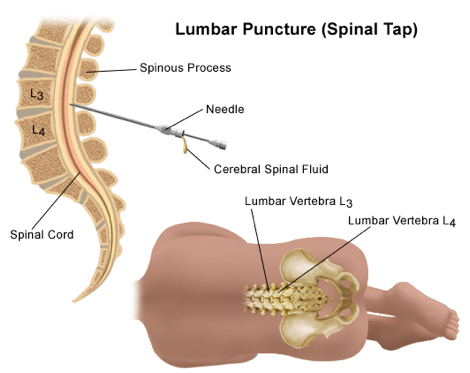

Positioning for Lumbar Puncture

Question to Author: Do we have permission to use this image?

The next step is to position the patient. (fig 1) You may need to treat pain first to facilitate patient comfort and cooperation. Infants and young children will be in the lateral decubitus position, laying on the left or right side. Infants can be held by another person with care taken to ensure the patients respiratory status is not compromised by curling the infant too tight.

Adults and larger children are positioned on their side and asked to curl their back out like a cat arching, with their knees brought towards the chest and chin tucked down. Adjust the hips and shoulders perpendicular to the bed without any twisting of the spine. Adults can also have the procedure performed in the sitting position with their legs over the edge of the bed, back arched out and chin tucked, offering a pillow to hug can help keep patients in this position. This can make it easier to find landmarks in obese patients, but opening pressures cannot be accurately measured in the sitting patients.

Good positioning and landmark identification is THE KEY to performing the procedure successfully.

To identify your landmarks palpate the anterior iliac crests, an imaginary line connecting the two iliac crests crosses the L4 spinous process. Palpate the spinous processes at the level of this line, carefully identifying midline. The spinal needle should be introduced at the L2-L3, L3-L4 or L4-L5 interspace. Mark the interspace at midline with a skin marker or by indenting the skin with the needle cap.

Prep and drape the patient using sterile technique. Clean at least a 10cm area with betadine or chlorahexadine scrub using a circular motion. If the kit comes with premade drapes, use the solid drape between the back and bed and the fenestrated drape over the back. Sterile towels can also be used.

Using 1% or 2% lidocaine provide local anesthesia. Palpate the landmarks and insert the anesthesia needle in the same space, initially making a subcutaneous wheel and then directing the needle into the interspinous space to provider deeper anesthesia. Probing with the anesthesia needle can also help identify locations of spinous processes when they are difficult to palpate. Ultrasound can also be helpful in locating bony landmarks in morbidly obese patients

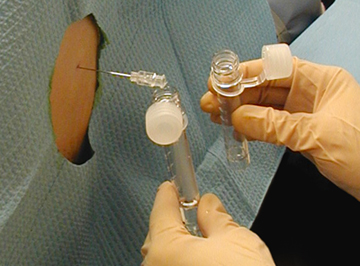

Prepare your manometer and collection tubes. Many manometers come as two pieces that need to be connected. Connect the manometer to the three way valve at the vertical position, the knob on the valve points to the port that is off.

Use the side of your non-dominant hand to brace against the patient’s back and stabilize the tip of the needle between your index finger and thumb. Use your dominant hand to apply pressure and advance the needle with the stylet in place. The bevel edge of the needle should be parallel to the ligament fibers that run head to toe. The bevel will be up when the patient is on their side and to the right or left when they are sitting upright. The needle will point slightly caudal, towards the patient’s umbilicus (see Fig).

Proceed through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament and finally the ligamentum flavum. It is often possible to feel a pop when going through the ligamentum flavum. Remove the stylet and look for flow of CSF. If no CSF is present slowly advance the needle 1-2mm at a time and remove the stylet and look for flow of CSF. If the needle hits bone superficially it likely has hit a spinous process and needs to be redirected rostral or caudal. If it contacts bone deeper, it more likely has contacted a transverse process, indicating the needle needs to be redirected in a right/left direction. Be sure to retract the needle into the subcutaneous space without removing the tip from the patient and redirect the angle before readvancing the needle

Once CSF is visualized attached your manometer to the needle and allow the fluid to flow and measure the pressure. Use one hand to stabilize the needle, slight variations occur with respiration. Normal pressure for adults is in the range of 7-18 cmH2O. Use the collection tubes to obtain approximately 1ml of fluid per tube. (fig 2)

Obtaining Fluid from Lumbar Puncture

Replace the stylet before removing the needle from the patient. Clean the site and apply a clean dressing. There is no convincing data to support a recommendation of bed rest after the procedure, however most practitioners have patients lay flat for one

hour.

Lab studies

Inspect the fluid by holding it in front of a white piece of paper in good light.

Is it turbid, cloudy or bloody appearing? Order lab analysis as follows:

- Tube 1: Cell count and differential

- Tube 2: Gram stain, bacterial and viral cultures

- Tube 3: Glucose, protein, protein electrophoresis (if indicated)

- Tube 4: Second cell count and differential.

- Tube 3 or 4 can be used for special tests or additional cultures

| CSF Interpretation | ||||||

| Glucose

(50-80mg/dL) | Protein

(15-45mg/dL)

| WBC

(<5cells/uL) | RBC

(0-500 cells/uL*) | Other | ||

| Bacterial Meningitis | Low | Elevated, >50 | Elevated 500-10,000, PMN predominance | Normal | +Gram Stain, High opening pressure | |

| Viral Meningitis | Normal | Normal to slightly elevated | Elevated, 6-1000, Lymphocyte predominance |

Variable | High RBCs can be seen in herpes encephalitis | |

| Tuberculosis

| Low | High | High | Normal | ||

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | Normal | Normal | Normal | High

+xantho-chromia | If tube 4 is less than 500 cells/uL most likely traumatic* | |

| Guillan Barre

Syndrome | Normal | High | Normal | Normal | ||

| Multiple Sclerosis | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Oligoclonal bands on electropheresis | |

* the normal number of RBCs in CSF is zero, but traumatic taps are common due to the epidural vascular plexus. There is no clear consensus on “how low is acceptable” when evaluating for SAH. The number of RBCs should decrease from Tube1 >

Tube 4. Correlation with clinical suspicion is often needed, and the tap may need to be repeated.

Complications

- Post LP headache, most common (10-30%). Results from lower CSF pressure or continued CSF leak. Usually responds well to IV caffeine therapy or epidural blood patch.

- Very rare. If rapid neurologic deterioration following LP, reimage the patient immediately and consult neurosurgery. See “special considerations” below.

- Epidural or subdural hematoma. Develops hours to days after procedure. Always assess for this in patients returning to the ED after recent LP.

- Epidermoid tumors

Special considerations

- Generally, an LP can be performed without a prior head CT in neurologically intact patients. The reason to do a CT first would be to rule out a mass effect that might increase the chance of herniation following CSF removal. There are a few patient populations that warrant a CT head prior to a LP: patients at higher risk for intracranial mass. This includes immunocompromised patients such as patients with HIV, and patients with a focal neurological deficit, depressed mental status or with papilledema. A CT does not completely rule out the possibility of increased intracranial pressure.

- If suspicion for CNS infection is high, do not let performance of an LP delay the administration of appropriate empiric antibiotics. Pretreatment with antibiotics might decrease the yield of fluid cultures. Delaying treatment in severely

ill patients will be detrimental to their outcome!

References

- Euerle B. 2013 Spinal Puncture and Cerebrospinal Fluid Examination (60). In Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine.

- Reichman E. 2004 Lumbar Puncture (96). In Emergency Medicine Procedures.

- Silver B. Lumbar puncture. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 25;356(4):424-5

- http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMvcm054952 NEJM Videos.

- Lumbar Puncture (n.d) In UCSF Procedures Training. Retrieved from http://sfgh.medicine.ucsf.edu/education/resed/procedures/lumbarpuncture/

- Doherty CM, Forbes RB. Diagnostic lumbar puncture. Ulster Med J. 2014 May;83(2):93-102.

- http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/test_procedures/neurological/lumbar_puncture_lp_92,P07666